The emergence of instrumental music as an independent genre from its earlier function as primarily a support for (or elaboration of) vocal music takes a large step forward at the dawn of the seventeenth century. Specifically, dances, which were invariably heretofore the most significant forms for which purely instrumental music was suited, continued to be one of the sources of inspiration for Baroque composers regarding their conception of structure. Many of these dances, such as the Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, Minuet, Gigue, etc., were cast in binary forms. Eventually this structure itself became independent of the dances that they were originally associated with and composers have continued to use binary forms in subsequent eras to give cohesion to vastly different musical materials.

In essence, binary form consists of two repeated sections, A and B, which have close musical ties in regards to motifs and textures. In many cases, when in a major key, the A section will cadence in the dominant while the B section will begin in the dominant and return to the tonic by its conclusion. Similarly, when in a minor key, the A section often will cadence in the relative major while the B section will begin in the relative major and return to the minor key tonic by its conclusion. While there are many binary form pieces in the literature in which each section was of equal, or near equal length (as with the dance movements), this is not a prerequisite as there are also numerous examples in which the B section greatly outweighs the A. In such cases, the B section can begin to take on a developmental character, and can be considered a precursor to the sonata.

For our study of binary form, we will begin with a step-by-step composition followed by two completed works exemplifying the techniques of the genre, a minuet and allemande.

In the example below, we will explore various techniques to develop material sufficient to compose a piece in binary form. Remember, as composers we usually cannot only rely on raw inspiration to sustain an entire work. We can, however, draw on a multitude of established methods to transform musical materials. Part of our goal is to create while maintaining an organic unity throughout our work. As such, the techniques we will learn should allow us to write more extensively with only a minimum of original material. When we apply these methods artistically, they can themselves inspire new ideas rather than simply provide a mechanism with which to manipulate them. One mark of a strong composer is the ability to create something unique and emotionally satisfying by using traditional, and perhaps even conventional methods in novel ways. Techniques and ideas explored in this example include:

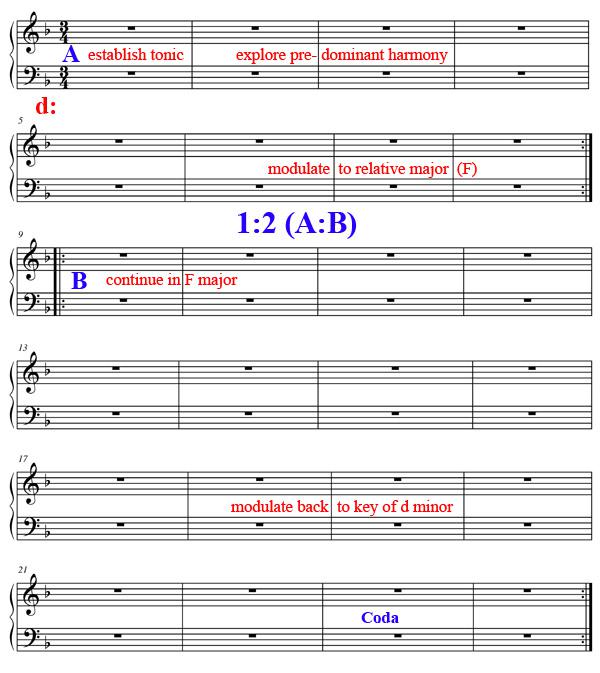

Outline. To compose a binary form piece ourselves, we need to begin with an overall sense of the structure of the piece, both in terms of the length of each section and the harmonic regions we will be working in. For our piece, we have decided to make the B section twice as long as the A section and tack on a brief coda (or closing section) at theend. Next, we determined the key and meter (d minor and 3/4 time). Without going into too much detail, we can sketch in some harmonic ideas and approximately when they will occur.

Motive. Next we need to generate some initial musical material with which to create. We can begin with a motive, which is a compact musical idea that has a distinct profile so that the listener can distinguished it as it is developed throughout the composition. A motive normally consists of a rhythmic idea, a melodic idea, or a combination of both. It’s repetition and modification over the course of the piece will provide the listener with a musical element with which to identify with, similar to how we follow a character in a play that goes through some kind of drama and ultimate transformation.

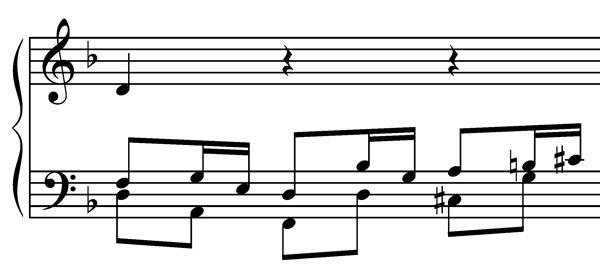

Here we have established a bar-long rhythmic motive.

b. Next, we have spun a little melody around this rhythmic idea to best establish our home key of d minor.

c. Finally we can harmonize the motive and complete the first bar. Note that we have engaged three layers of different kinds of activity. Transferring the rhythmic impulse from voice to voice (as we can observe between beats one and two, from the soprano to the alto voice) is crucial to sustain continuity and momentum, which is at the root of this style of composition.

Motivic development. In bar 2 the rhythmic dimension of the motive is maintained in the soprano while the contour of the melody is changed. However this will not disturb the continuity with the first bar but will reinforce for the listener the relevance of the rhythmic design as being main material. Note as well we have redistributed the activity between the lower two voices: the alto progresses in broader quarter notes as the bass did in bar one, while the bass introduces a new motivic idea based on a descending scalar pattern and picks up the rhythmic impulse for the second half of the bar.

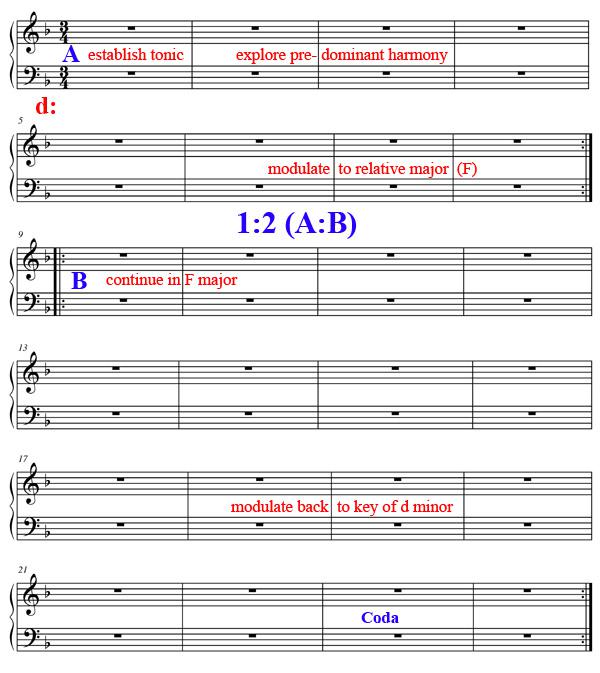

Textural Change. In order to bring variety to the texture in bar 3, we can drop out one voice and have a duet between two chosen parts (in this case the soprano and alto). In addition, to avoid needless repetition of the main motive in its entirety, we can take a portion of it and use that as the basis for development. This process, known as fragmentation, can substantially increase the sense of motion in the work. A related technique, liquidation (coined by the 20th century composer Arnold Schoenberg), progressively eliminates portions of a motive and further compresses the rate at which material needs to be processed by the listener.

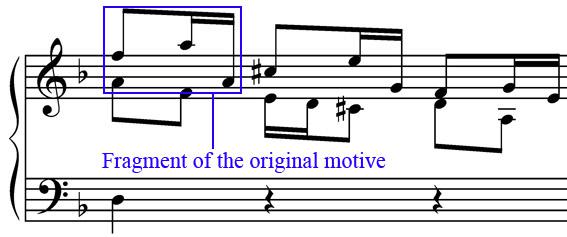

Voice exchange. One often-overlooked aspect of composition is the rate at which the attentive listener needs to process musical information as it is manipulated and developed while new material is introduced. At certain points in a piece the listener needs what can best be thought of as moments of relaxation – when the music continues to push forward yet does not do so in a mentally taxing way. One technique to accomplish this is using a voice exchange. Here the composer reuses previously heard music with little or no alteration and simply rotates which voice articulates the earlier passages. In bar 4 of our piece we have taken the main motive from the soprano and dropped it into the bass voice and vice versa.

Another Duet. It is equally important for the composer to develop textures as well as motivic and harmonic materials. With this in mind, we can compose another duet in bar 5 with similar content as the previous one in bar 3.

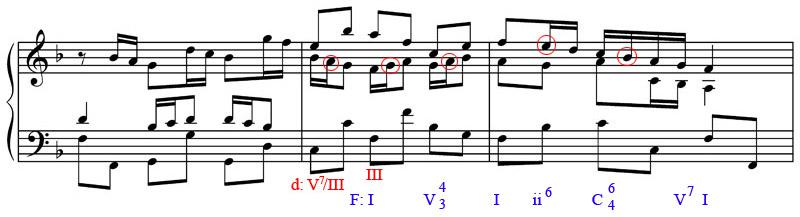

Modulation and Climax Notes. The primary transformative technique in tonal music in regards to harmonic motion is modulation. Whether it be unexpected or by way of a smooth segue, and to a distant, chromatic key relationship or to a closely related diatonic scale degree, a shift in tonality can be refreshing for the listener. In our piece, we use a secondary dominant to modulate without disrupting the flow of the music to the relative major (F major) in bars 6-8. As well, the use of a single climax note will bring with it heightened attention to a given moment. With this in mind, and to emphasize the importance of this passage, a high Bb becomes the zenith of the A section. It is important for the composer to remember these climactic passages when thinking about the larger sense of drama over the course of the entire composition – we will have to bring the work to even greater heights in the following section to fulfill the dramatic needs of the work.

Imitation. As a further aid to the development of our piece we can draw on secondary material from previous passages and bring them to the fore. To open the B section (bars 9-12) we have taken an earlier accompanimental figure from an inner voice (from bar 6) and make it into a figure that will become a point of imitation. Similar to the entrances of a fugue, this little melodic idea is passed around from voice to voice and transposed to scale degrees that best support the harmonic progression.

Sequence. Previously we discussed the need for points in a composition where the composer can to provide the listener with brief periods of time to ‘relax’ the ear from continually needing to absorb, digest, and assimilate complex manipulations of the musical materials, while still providing ample momentum to the overall flow of the piece into the next passage. One musical construct that can afford the composer with a simple way of achieving this is the use of a sequence.

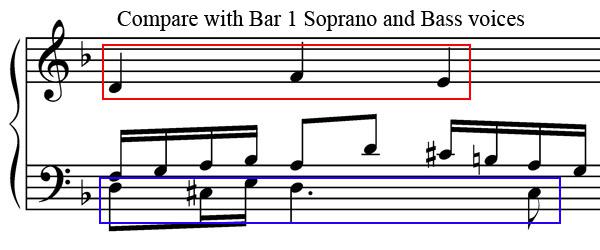

Here we have articulated a four step, diatonic sequence that ascends to the climax note of the entire composition, a high C (recall that in the A section, Bb previously marked the climax, and for the sake of drama, we have exceeded this in the B section). As well, this occurs at the golden section of the work. The golden section refers to the ratio of (approximately) 1.6 that has long been regarded as one possessing certain natural aesthetic properties. In our piece of a total of 24 bars (not including the single concluding bar after the repeat of B), the climax occurs at bar 15, or a proportion of 1.6. Therefore, this moment should innately feel to be at the ‘right’ point in the piece by the listener. The connection of this moment with another motive in the piece is notable. Recall the descending scalar passage from bar 2 in the bass – here it is used as the culminating element of the second section. As well, the rhythmic congruence between the soprano and alto voices in beat two of bar 15 adds to the excitement of the moment.

Bars 12-16.

Concluding Passages. A brief recapitulation of the opening three bars occurs after our return to the original key of d minor. The bass part is made more elaborate here to provide additional rhythmic activity and forward motion as the piece nears its conclusion. This seamlessly connects to a brief coda (or closing section) that consists of new material based on the motives of the piece. One last technique is introduced here to connect the coda with an earlier idea: melodic inversion. Melodic inversion occurs when the contour of a line is flipped. The scalar motive from the bass part in bar 2 is inverted and articulated in the bass and tenor voices in this final passage.

Complete Composition.

Listen: Track 2

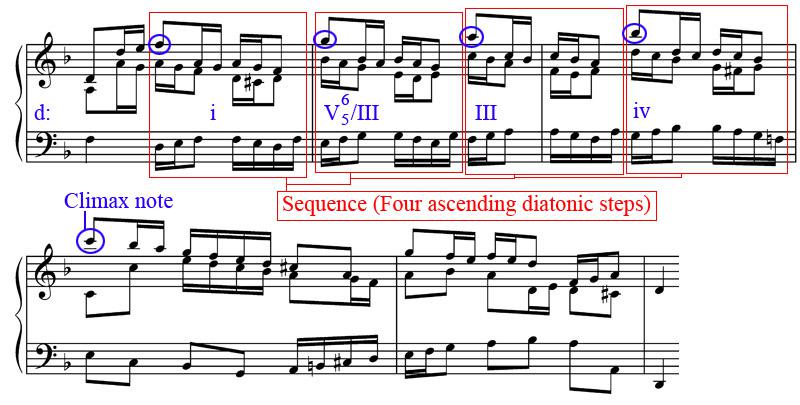

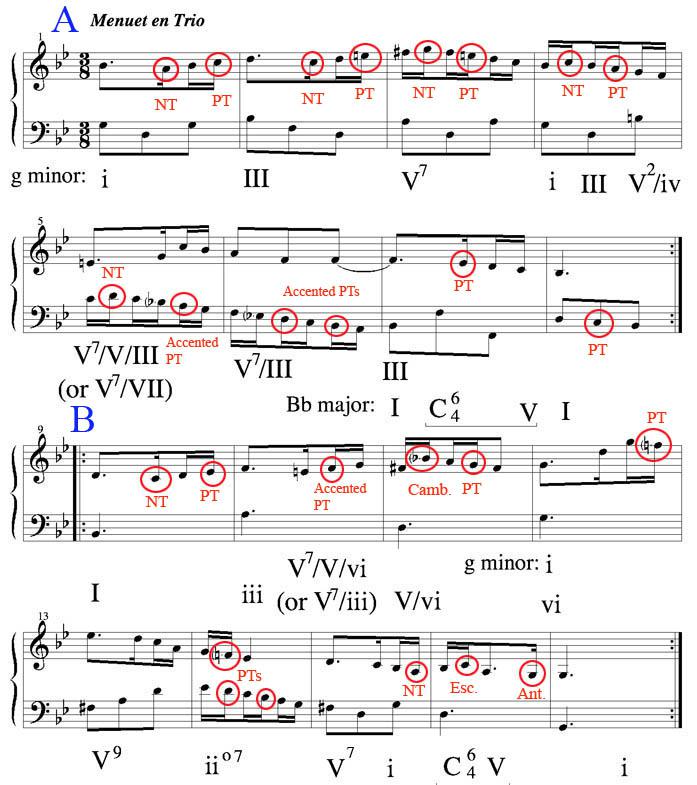

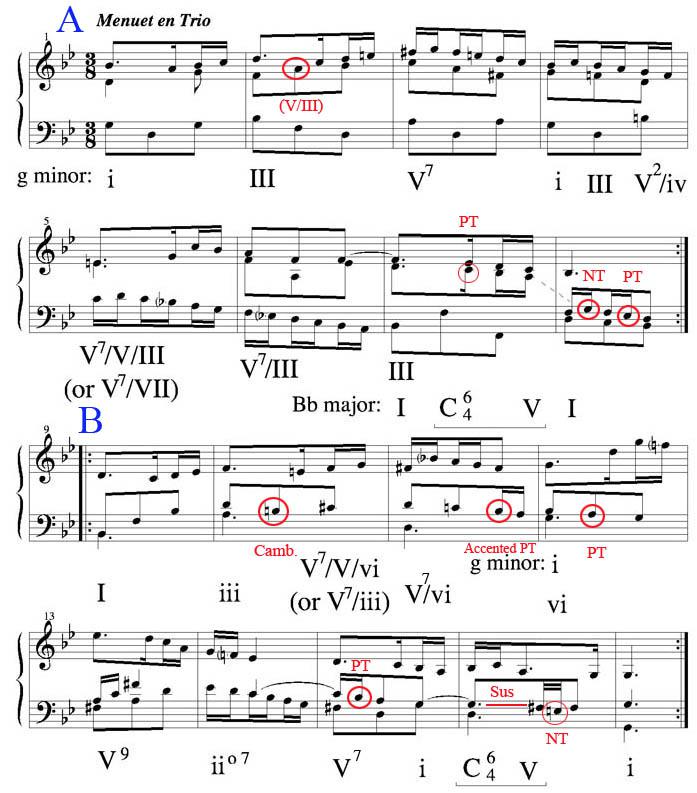

In the following example, we will create a French-styled Minuet (called a Menuet) in three voices in a minor key.

Although in a three part composition such as this it is not absolutely necessary to begin with only two voices, the student is encouraged to keep the texture less complicated at the outset. One good practice in composing binary forms is to set up your score so that you are drafting both the A and B sections simultaneously, allowing each phrase to draw on material from the other to ensure musical unity. Notice, for instance, the melodic material in bars 1-2 is identical to that in bars 9-10, save for their starting pitches. In bars 1-2, we are establishing the g minor tonality, while in 9-10 a Bb (relative major) tonal center must be adhered to. Notice too that the rhythmic activity is transferred to the bass in bars 5-6 as well as 14 to allow for variety in the texture.

Of particular importance are the two modulations that occur in bars 6-7 and 11-12 to the appropriate key regions. Note that these transitions can occur at varying places within the sections. For instance, here the first modulation occurs mid-way in A but very early in B. To reinforce these modulations, tertiary dominants (or the dominant of the dominant of the new key) are employed in bars 5 and 10. These are immediately resolved correctly to secondary dominants that lead to the new tonal centers.

Note: Most chord indications here do not specify inversions – this is not as relevant to the course of instruction here where harmonic regions in which the materials are functioning is of primary importance.

Next, a third voice is added in between the two parts already composed. The student shouldn’t feel obligated to preserve the original lines without any changes – more often than not, with the introduction of another voice, new ideas will inspire the composer. However, the harmonic implications that have already been established should be maintained to a strong degree. Note too that this third voice here acts mostly in a supporting role, filling out harmonic implications and tying together the textures of the other voices; it never becomes a strong melodic component.

Listen: Track 3

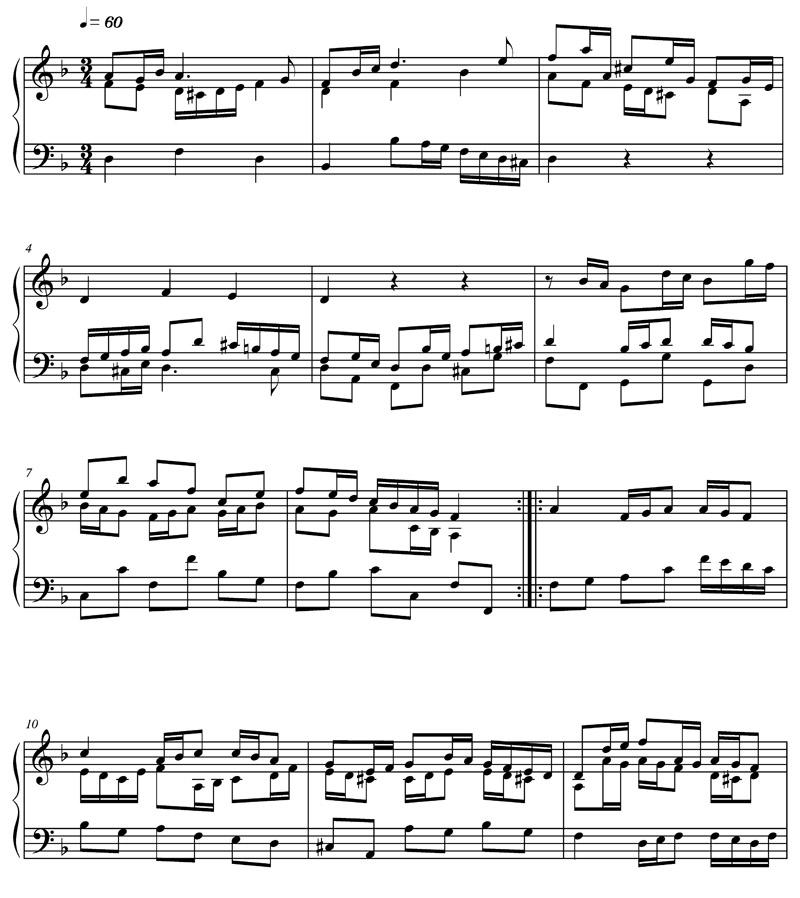

In the following example, we will compose a three voice Allemande in a major key. The principles involved are largely the same as with the Minuet, except since we are in a major key, the A section will conclude with a modulation to the dominant and the B section will begin in the dominant and modulate back to the tonic. In addition we will experiment with the usual binary structure in two ways: a) the A and B sections will be asymmetrical, with the B section being somewhat longer and developmental in content; and b) the B section will have a first and second ending wherein they will both possess an identical harmonic progression, but with the second ending having a more ornamental texture.

Regarding the teaching of composition in general, it remains an important aspect of the learning process for the student to be encouraged to experiment within a particular musical vocabulary once the foundations of that style have been well established. After all, this is what distinguishes every significant composer throughout the history of Western music. Therefore, with this in mind, our piece will employ some unique harmonic progressions, each built on relationships falling well within the language of the Common Practice.

Since the manner and materials of the binary form have been explained during the study of our model Minuet, we will comment here only on those points of interest that depart from what we already understand.

Despite the fact that the tonic and dominant are the pivotal key regions in a traditional binary form composition, intermediate key regions should not be avoided. Notice in the

A section the piece briefly modulates to the relative minor, while the B section (which begins in A major) temporarily modulates to its own dominant of E major before eventually returning to the tonic.

In bar two the V/IV should of course resolve to IV (G major triad), however, although the following chord is yet another secondary dominant, it does contain a B, D, and a chromatically altered G(#).

As well, this next secondary dominant refuses to resolve to the expected sonority of V (A major triad). Instead, it creates a transition to the relative minor by using the B, E, and anticipatory C# as common tones to the iiø2 of the new key region.

A secondary dominant to an altered chord can create a unique moment in the perception of the listener. Here we have employed a secondary dominant to the Neapolitan (bII), which in turn emphasizes the resolution to the dominant in bar five.

A dramatic moment is created as the downbeat of bar eight is approached through contrary motion between the left and right hands. This moment is emphasized by the fact that the climax note of F# is a dissonance.

The interlocking sequences in bars ten and eleven culminating a series of secondary dominants create the most sustained point of drama in the piece, leading to a compression of the harmonic rhythm and eventual coda.

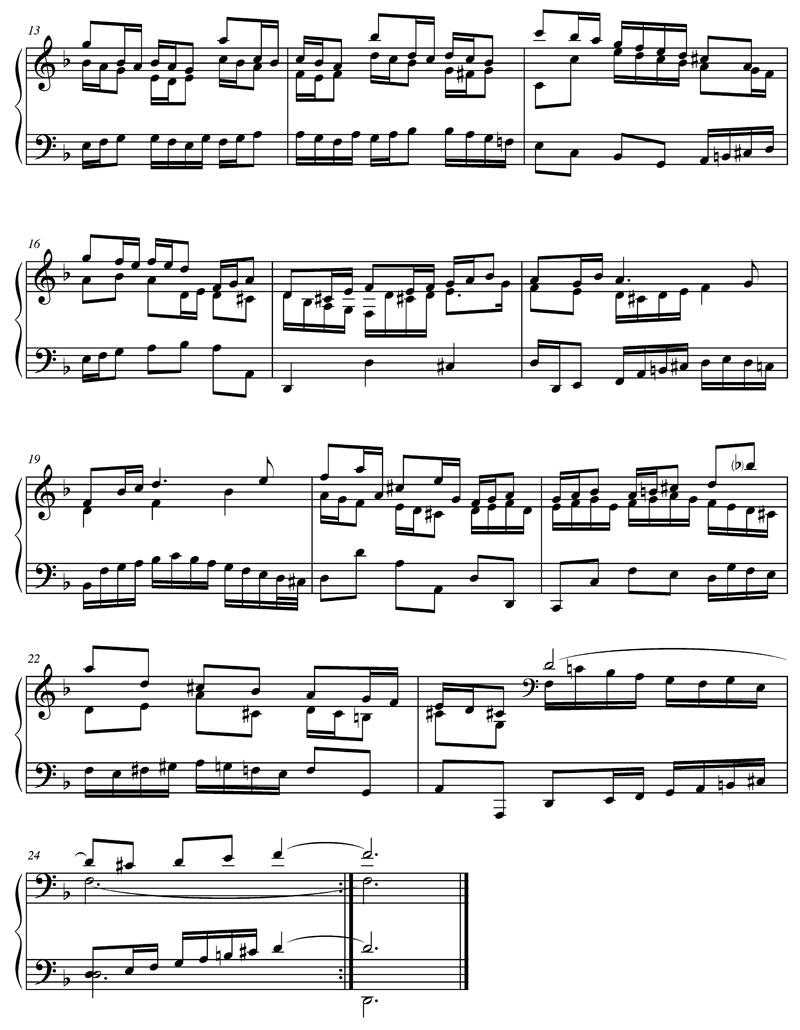

The elaborate second ending is prepared and executed in stages. The use of sixty-fourth notes has already been established in the A section, albeit only briefly. Therefore, we reintroduce it gradually, mixed in with other note values in bar fourteen, before allowing them to flow freely in the final flourish. If we compare bar eleven to fifteen, we notice that the original sequence has large leaps between each beat. This allows us to fill in those spaces in the second ending when all the note values have been halved. Also note that the high ‘a’ towards the end of bar fifteen is used to set up the climax of the B section in bar sixteen with the single high ‘b’. The ‘b’ is emphasized even more through its preparation through leap rather than the steps that have been defining the passagework up to this point.

Listen: Track 4